Following up a film like Parasite, which began its awards circuit run with the Palme d'Or at Cannes Film Festival and ended by becoming the first non-English film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards, is a daunting task. Many expected director Bong Joon-ho’s next film to follow in Parasite’s footsteps — a tight, family-centered thriller with sharp economic commentary and darkly comedic beats that shocked American audiences and thrust Joon-ho’s work into the Western mainstream.

Instead came Mickey 17. The choice to adapt Edward Ashton’s 2022 science fiction novel Mickey 7 may alienate some viewers, but fans of Bong Joon-ho’s work will immediately see the connection. With Mickey 17, Joon-ho returns to his uniquely wacky brand of sci-fi à la The Host and Okja. Whereas his previous films centered broader critiques of capitalism and environmental issues, Mickey 17 is laser-focused on the political climate of our times. For many reasons, Mickey 17 certainly won’t be for everyone, but I believe that it may be one of the most important movies of the year.

Mickey 17 is set in 2054 but, excluding its technology, its world doesn’t look much different than our own. The film follows Mickey Barnes (Robert Pattinson), a normal man with a streak of bad luck that ends up on an expedition to colonize the planet Niflheim. Amongst politicians, security agents and pilots, Mickey secures his way off Earth by becoming an Expendable. He is constantly sent on lethal missions and reprinted after each inevitable death. Now on his seventeenth iteration, Mickey ends up surviving a mission that should have killed him — and finds himself face-to-face with Mickey 18, printed in anticipation of his death.

Bong Joon-ho is less interested in the scientific parameters of this not-so-distant world, and more in the political and ethical implications of cloning. He centers these questions of morality on Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo), a former governor who failed to secure re-election (and who is not-so-subtly surrounded by a group of red-hat-wearing sycophants) and has now been chosen to lead a church-sponsored colonization mission to Niflheim. In one of the most telling scenes of the film, Marshall declares that while cloning is a sin, there is economic benefit in using the technology on their upcoming trip — thus, the Expendable program.

The political commentary of Mickey 17 is anything but subtle, but in my opinion, Bong Joon-ho’s critique is a response to current times. The world we’re living in is nearing the absurd — shouldn’t the art we make in response be just as ridiculous?

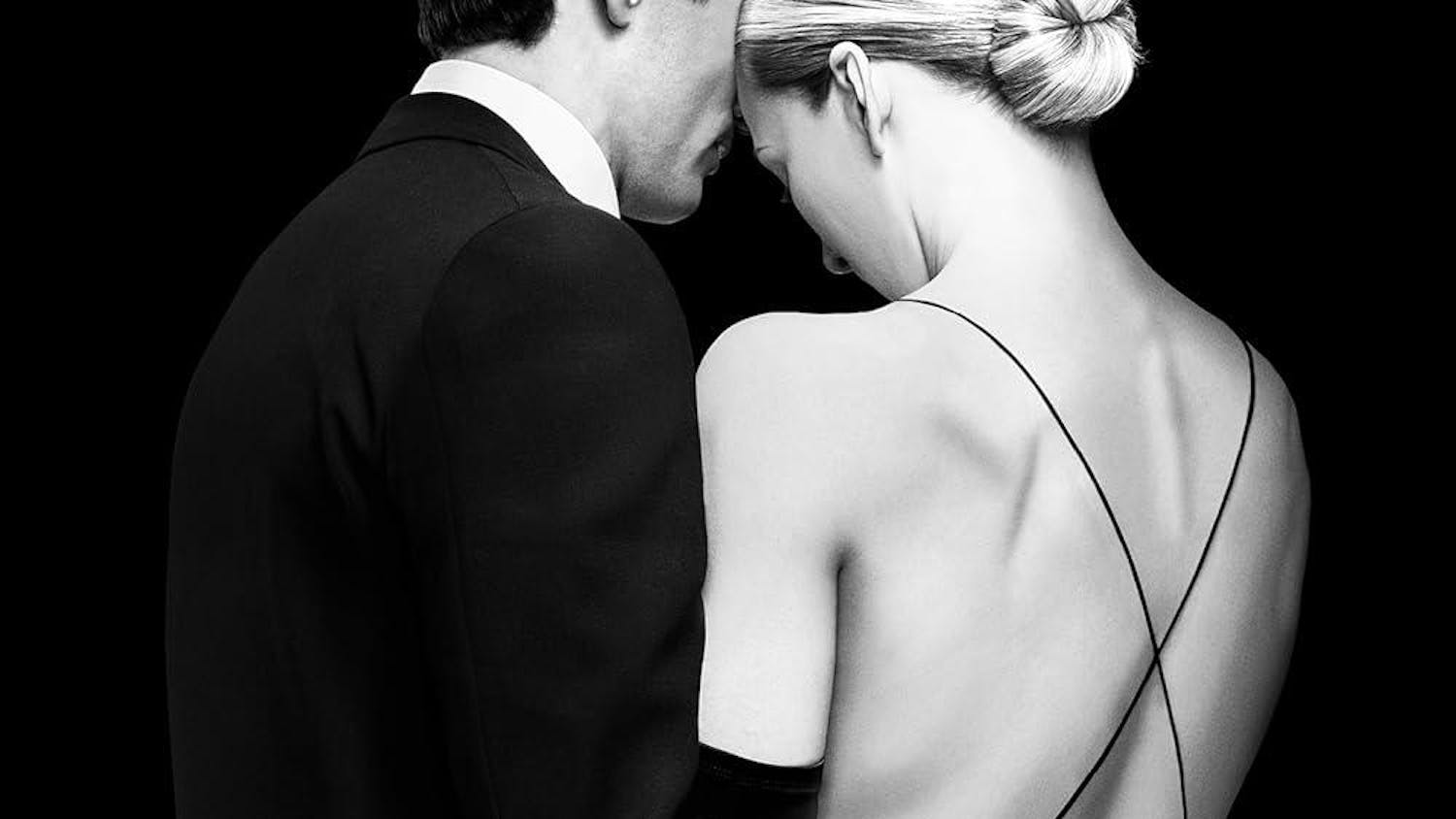

This isn’t to say that the film lacks heart. At the core of the film is Mickey, a real human being whose status as “expendable” has relegated him to the bottom of society, to the point that he starts to believe it. It is only his relationship with security agent Nasha, played by Naomi Ackie, that reminds him of his own humanity. Here, the film’s message is clear — it is love that makes us human, and love that gives us the power to resist. The film is able to navigate between its moments of absurd humor and its much deeper reflections on humanity in part because of Robert Pattinson’s incredible performance.

These accolades won’t come as a surprise to anyone who knows me — Robert Pattinson is my favorite actor and has been since I first fell in love with film. But despite having seen his entire filmography, Pattinson’s performance takes turns I have never seen from him before. Mickey does not transform over the course of the film, but instead is split into two halves — 17 and 18 — who, despite being created from the same DNA, are vastly different. Whereas Mickey 17 has accepted his status as “expendable” as a punishment for his past wrongdoings, Mickey 18 is full of anger for the system that has entrapped them. Pattinson’s ability to play these two wildly different characters, while still retaining the core of what makes both of them Mickey Barnes, is what makes the film work.

Mickey 17 may be a little rough around the edges and admittedly unsubtle in its messaging, but so is what it’s responding to. Bong Joon-ho isn’t trying to be subtle. Mickey 17 is a desperate scream into a political climate that seems, at times, completely absurd. Don’t go into Mickey 17 expecting Parasite — you may end up wildly disappointed. Instead, I hope that audiences go into the film with an open mind and allow Bong Joon-ho the chance to make more wildly entertaining, and yet politically important, films like this.

Nicholas York is a sophomore in the School of Industrial and Labor Relations. He can be reached at nay22@cornell.edu.

Nicholas York is a member of the Class of 2027 in the College of Arts and Sciences. He is a staff writer for the Arts & Culture department and can be reached at nyork@cornellsun.com.