Spanning decades of well-versed knowledge in the dynamic nature of ecology, researcher and Prof. Marc Goebel, has brought his unique experiences to Cornell’s Introductory Field Biology course, NTRES 2100, as an instructor for the past 11 years. His mission to prepare students for life beyond the class has contributed to an unparalleled curriculum identity.

Exploring diverse climates, native species and applied research project collaboration, students are invited to expand their perspectives with concepts building deeper connections to the planet and leaving a transformative impact.

Teaching in the Forest: Bringing on a Wealth of Knowledge

Always fascinated by the links between different fields in nature, Goebel is a native of Germany where he studied forest science in Munich and then embarked on a unique journey to Seattle for the master’s program at the University of Washington.

During five consecutive summers, Goebel had the unique opportunity to set up a program with two research faculty members as part of a Field Experience for International Students in the unique backdrop of the Pacific Northwest climate where he learned to teach across multiple ecosystems. From temperate rainforests and high mountains in the North Cascades to estuaries of Puget Sound, encountering these “regions of contrast” built comprehensive exposure to instruct in complex ecotones. After receiving his Ph.D. from Pennsylvania State University, he began a dual career as a senior research associate and senior lecturer at Cornell.

“I got so fascinated to not only convey this knowledge from books, but to convey it actually in the field.” Goebel said.

From Field to Figure: An Unparalleled Curriculum

What began in 1977 as a course on agriculture and forestry, NTRES 2100 has evolved to be more suitable towards natural resources for the climate of today, adapting alongside the progression of science to create a broader education for field biology students. A strong focus on organisms in Ithaca has given students a sense of place within their community beyond ecology. Each year, students are tasked with knowing the names, morphology and characteristics for a myriad of local tree, insect, bird, reptile, amphibian, fish and mammal species.

“What is important is giving students a base, and then having the ability to link it to sense of place.” Goebel said.

To develop a strong foundation for physiological properties, students must observe them first hand. Housed in the same area as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, close partnerships with the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates provides access to an array of collections to demonstrate organismal concepts in physical detail. For tree identification, students can turn to the 860,000 preserved plant specimens from the Herbarium of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium to practice the pressing process and study leaf characteristics.

Visiting these facilities and utilizing vast resources from past to present, adds a historical facet to how genetics have changed over time. These relationships have built a strong basis of knowledge, shaping a refined interdisciplinary education in the forever-evolving climate.

Goebel and former Prof. Paul Rodewald, now retired, originally began co-teaching NTRES 2100 together in 2014. Learning an abundance of content in one lecture and twice weekly field labs can be challenging for students to grasp, which inspired both professors to introduce the research project aspect into the course as a double structured curriculum.

From examining macroinvertebrates in the stream to observing birds in trees, there is flexibility for students to dive deeper into something they are more interested in investigating. Complementing lab teaching with data literacy and collection allows exploration into the processes of what the information really means.

“From field to figure … that is what field bio is.” Goebel said.

When taking on the course as a solo instructor in 2020, Goebel incorporated the teamwork element into research projects. Emphasis on collaboration was further developed alongside post-doc Kira Treibergs from the Active Learning Initiative under the Center for Teaching Innovation to aid improvements in teaching and learning.

Students are applying the same idea of collecting data from the field, getting results, presenting them, and learning to construct a final written report while dealing with the realistic conditions of group research viewed from multiple angles. This is an upfront snapshot for not only carrying out the project, but understanding how difficult the process can be with considering different facts, gaps in data, and dealing with site management issues. Linking findings to existing results in a published paper allows comparison of trends from a professional base despite limitations with timing and equipment.

“The goal is not to be perfect, the goal is to learn.” Goebel said. “We should always be improving.”

Whether students are waist-deep in Oneida Lake at the Cornell Biological Field Station at Shackleton Point or trudging though the deep woods of the Arnot Teaching and Research Forest, hearing from experts and exploring the environment throughout iconic field trips have also enhanced how experiential learning is done outside scheduled class time. Pairing the curriculum with action-packed, highly intense and deeply engaging all-day and overnight adventures helps students contextualize their surroundings.

Landscape in Motion: The Bigger Picture

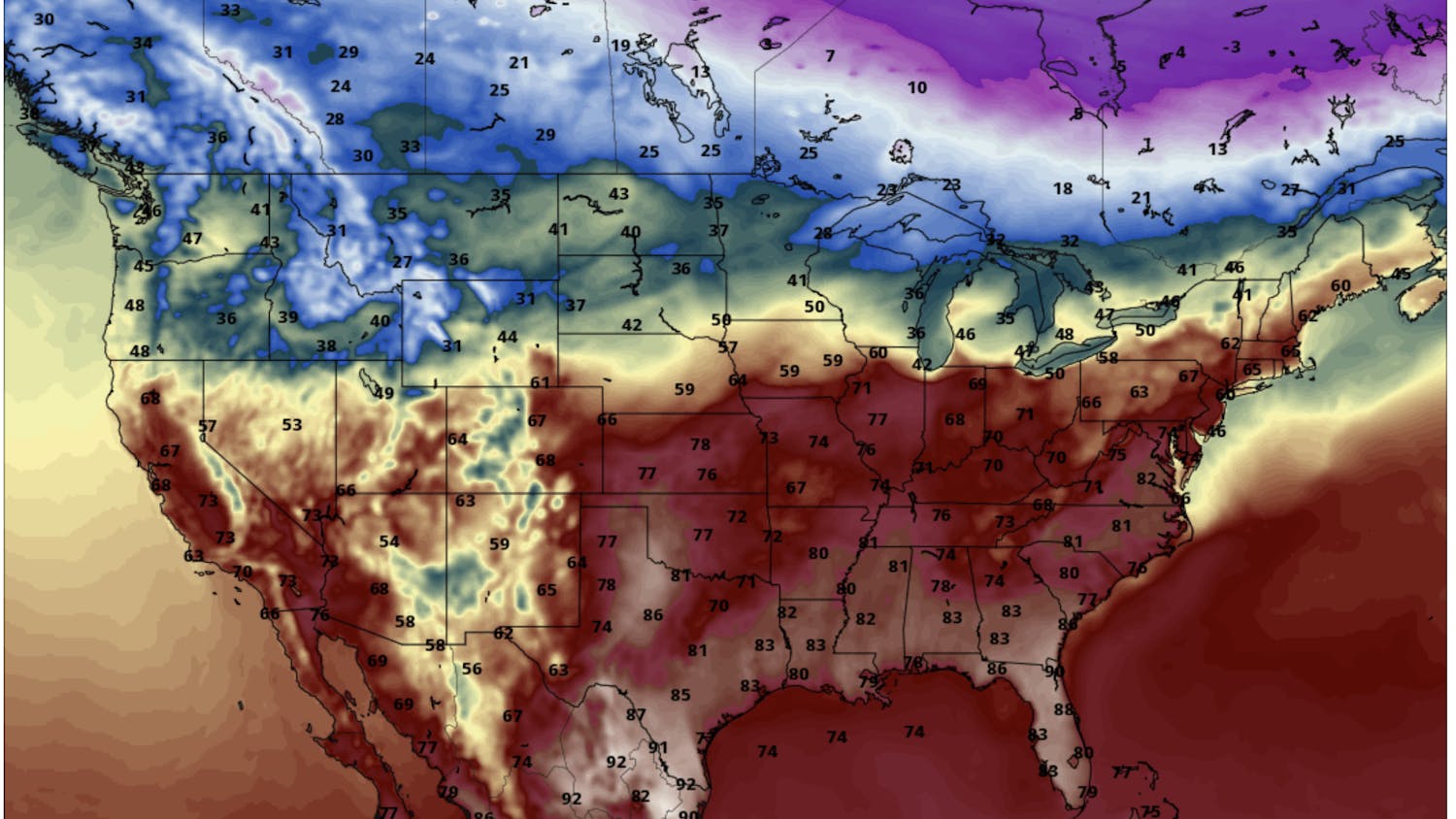

Students also visit and hear from earth and atmospheric sciences senior lecturer emeritus Mark Wysocki ’89, who currently manages the weather station at the Northeast Regional Climate Center on Game Farm Road. Environmental variables are integral to comprehending ecological interactions, with the addition of weather data in assignments highlighting the backdrop of connections to place.

Emphasis on time outdoors allows students to feel the world around them, like while walking during labs to see development forests at Turkey Hill and McGowan Woods, a hot spot for birding and on-campus natural areas of the Cornell Botanic Gardens. Stepping into old growth forests is like transportation back in time, where students can pick and position organisms in different succession stages.

Linking the vertical distribution of birds makes more sense when connecting it back to characteristics learned from specimen quiz review or songs heard on the bird walk at Arnot Forest. It gives a holistic interpretation of the final information conveyed from the introductory foundation. Bridging everything together — land, flora, fauna and weather — lets students glue puzzle pieces together to frame the bigger picture.

“In a changing world, field bio is essential to be grounded with your feet where you stand and what it means.” Goebel said. “Coming back to the bigger picture, you are learning as citizens of this planet – how important this is, without it you are not here.”

For Goebel, it is imperative for students to come out of the course being able to visualize the moving parts associated with growth stages of forests. He brings together curriculum basics in this manner to inform the meaning behind witnessing in the woods, rather than studying it from a book.

“Any CALS major should have a field course component or course to link your knowledge to the real world… about your home planet.” Goebel said.

Leading a legacy of nearly 50 years taught by a select few professors, the course’s longevity is also supported thanks to Cornell’s abundance of resources, which indicates the significance in past and present education while projecting how necessary it is to maintain for the future.

Carrying the Field Biology Toolkit Across the Globe

Past Environment & Sustainability students who had taken NTRES 2100, found the course to be a gateway experience for preparation in journeying abroad to Auckland, New Zealand, for the EcoQuest program during spring of 2024. Raymond Pan ’25 pitstopped along the coastline to analyze various sustainable agricultural industry operations, while Melanie Halko ’25, Anthony Pera ’25 and Hannah Lewis ’25, traveled to on-site coastal ecosystems with the ecology team where they got to explore the diverse habitats of coastal ecology and alpine mountainous regions.

The transition to international research was much more comfortable for Halko as she came in equipped with a foundational skillset from field biology. After identifying feeding locations for native bat conservation, Halko presented her research to New Zealand’s Department of Conservation Council and Auckland Council who now use that data to conserve bat habitats.

“One of my top classes that I took at Cornell … it gave me a lot of confidence to be able to go abroad somewhere where we’d be spending so much time outdoors in nature [which] also prepared me for the research and projects that we did.” Halko said.

Pera had worked on a methane project to measure wetland flux and estimate consequences of a new drainage system installed in a wildlife preserve, monitoring long-term climate change to assess natural gas emission impact in the area. Establishing this new trial program meant there was no previous protocol, so they were designing and implementing everything on the fly while keeping up with geographic information system groups or vegetation sampling. With prior experience from the course, improvisation is familiar to Pera having had the freedom to craft his own research project and go through the self-directed process in a controlled course setting for the first go-around.

“Designing your own experiment and carrying it out, writing a report on it and presenting it later, I used every single one of those skills for the Directed Research Program in New Zealand.” Pera said.

In an agriculture-focused program, Pan had the opportunity to improve financial sustainability of farms through land management. His group explored the orchard and fruit industries around the country and community gardens along the coastline to help local families with blended parcels of land. Despite examining different projects and business operations, the hands-on aspect of teamwork was utilized to achieve a similar goal.

With robust confidence, increased capacity to help others, collaboration as a research team and thorough exposure to working outdoors, an advanced field biology foundation from Cornell not only prepared these students but also brought greater meaning to their time abroad.

“[With] the bones of field biology and ecology that were already built up in my time at Cornell, I was very prepared for everything we did there.” Pera said. “I could really help out students who were learning these skills for the first time.”

Lasting Footprints on the Journey of Life

As recent graduates this past May from the E&S major under the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, students continue to resonate with takeaways from NTRES 2100 as they pursue their own careers to engage in field biology and other disciplines, carrying these experiences with them wherever they go.

“Going into the environmental sector with field bio was a great introductory way to get exposed to different environments, getting my hands dirty (quite literally).” Lewis said.

Confidence in fieldwork stems from the class, which served as a safe atmosphere to learn about the outdoors in a way that was realistic in representation for internships and jobs when entering the workforce. Whether students plan to complete a Ph.D. in Ecology or reframe natural resource laws on Capitol Hill, students believe the course has opened their minds to consider concentrations where fieldwork is involved. In addition to physical notes to recall from, students also leave with a mental archive to visualize the broader significance of ecological resilience.

“Field bio was definitely the course that [showed me] there is a lot more to E&S than I thought there was.” Pera said. “Forever having references to field bio from experiences, memories, assignments, and even field journals.”

In line with the aim of the class, students become cognizant of larger implications from relationships between topics like wildfires and succession patterns to always “... look at a forest and see a deeper meaning.” Pan said. Goebel’s goal is for students to continue their lives knowing this, creating a lasting impression of the “bigger picture” he teaches students to remember.

“If you could take just one of these environmental field classes to get some experience and connect with nature, I think it would make people a lot more empathetic for the changes our planet is facing.” Halko said.

Fluency in coursework outdoors not only welcomes critical thinking about the environment, but puts uplifting meaning behind why understanding ecological interactions matter to inspire a shared passion for protecting the planet. Just like the presence of a keystone species in an ecosystem, NTRES 2100 is a keystone course in any education. Being inside the immersive world of field biology is a lasting experience that will stay with students, bringing learning to life forever.