When the pen hits paper, something similar to the big bang happens: Black ink explodes on virgin paper, while molecules collide and combust with each scratch to reveal a creation — that of your own. The final piece — whether it be an exhausted sheet slashed with abrasive letters or a single sentence — is evidence of your presence, your entity and of your learning.

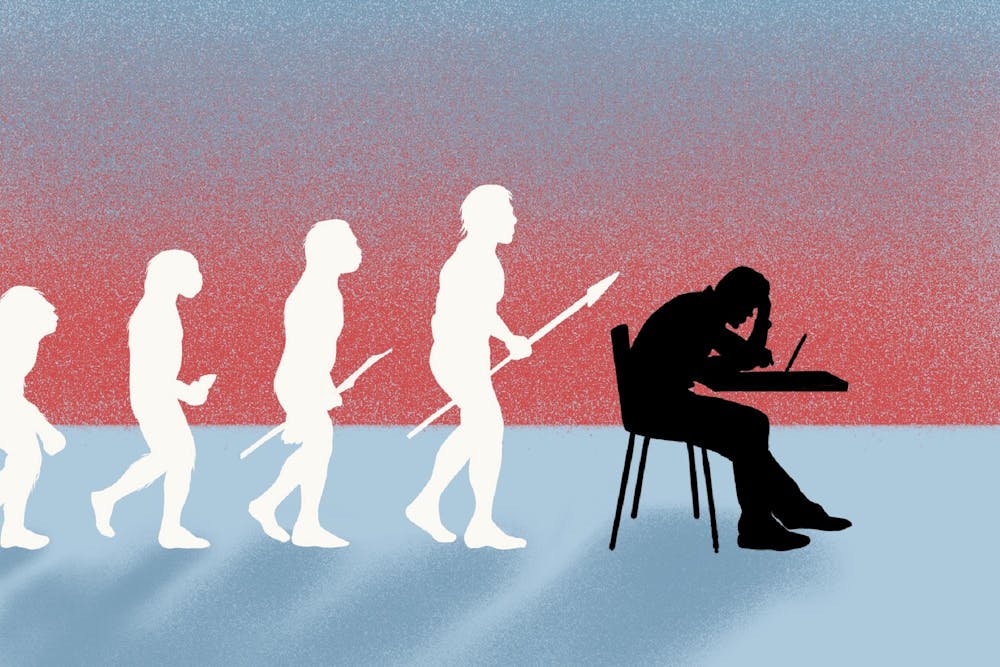

Once upon a time, the average day in class was exactly that — a pen, a paper and everything that comes in between. This archaic practice should be brought back — even if it prohibits laptops or the use of technology in classrooms.

In today’s classroom, however, the rasps of a pencil or whispers of paper have been replaced by the sound of cacophonous keyboards. Faces are no longer lit up by beige pages, but by a screen’s blue blinks. And when the unimaginable occurs — a professor forbidding any use of electronic devices — silent glances are exchanged amongst students, and all eyes blare with one emotion: frustration. I express perhaps an inward groan — get with the times. There was a time when I could not fathom a life without my laptop: my collection of all my works as a student, my dictionary and — I admit — oasis of New York Times puzzles.

Yet curriculums themselves were and still are heavily reliant on this digital machine; weekly online chemistry homework, textbooks, final papers, Zoom guest lectures, recordings and presentations all conglomerate into gigabytes. This fusion of technology and education reveals a frightening reality: The classroom is no longer essential to learning. Instead, with its digital expansion, education itself is no longer rooted within face-to-face discussions or lectures with peers and professors but instead hovers around in an imperceptible computerized cloud. With Canvas reminders of upcoming deadlines and a cluster of tabs collecting dust for a research paper, students are quite literally always “in” a classroom.

This simultaneous universality and inescapability of the “classroom” raises the question: How valuable is the actual class time, then? Participation, in most courses, is worth a meager 5 to 10% — a sacrifice most, including myself, are willing to make for an extra hour of sleep, sunlight or studies. As a matter of fact, reverse learning structures are particularly prevalent in STEM lectures, such as in Introductory Biology: Comparative Physiology; students are expected to essentially grapple with material individually while the allotted class time is dedicated to only practice questions. Additionally, Cornell boasts several asynchronous courses, such as General Physics I and II — testaments to the fading command and necessity of the traditional classroom.

This past year, however, three of my Literatures in English classes have reminded me of what a classical, authentic learning experience is — a rarity today that has been shrouded since the intrusion of technology into classrooms. While not all have totally banned laptops or other devices from being used, these courses did not even require them to begin with. Structured mostly around focused discussions and paper handouts of texts, the physical — and mental — barrier of a screen between student and professor was eradicated. I had forgotten what it had felt to learn in a raw, unpolished, intimate environment in which the physical books, paper and the space of the classroom ground me into my studies. This is no surprise, however — for years, studies have proven that learning with paper is much more effective than laptops. Why, then, do courses have such a stubborn loyalty to the latter?

With an over dependence on laptops, lectures themselves have increased speed. For most of my classes, I have always typed notes; now, as a senior, I can confidently say that as soon as I close my laptop, I can barely recall any of the covered material at all. To simply keep up with the speed of information, I do not process nor retain it but merely copy it. My Word documents of notes — albeit a hefty 20-pages — are false witnesses to the amount of material I truly learned.

Despite this flaw and ironic inconvenience of the laptop, however, I am unable to fully transition to note-taking on paper simply because the pace of lectures is much too fast — perhaps because the courses themselves are designed around this reliance on digital devices. Oftentimes, I would find myself at a crossroads: Do I risk missing information in a recording-less class, or do I go the safe, but unfulfilling route? The latter always wins; quantity has finally won over quality.

If more professors adopt this no-devices policy in their courses, however, perhaps this dilemma with the pacing will self-remedy itself. With slides, moving on to the next subject can be done with a press of a button. Without slides, the pace of the classroom instantly relaxes. The focus is no longer on a large screen, but on the face of the professor and vice versa. As for exams or essays, why not have them in person and on paper? Larger concerns about artificial intelligence and plagiarism could be remedied with a simple switch to the old-fashioned way.

In a classroom free from the digital hand puppeteering us all in our daily lives, everyone follows and writes the same letters, numbers or diagrams that curve across a chalkboard; ultimately, everyone is thinking about the same thing — a beauty in the nostalgic togetherness that the computer could never bring.

Serin Koh is a fourth year student in the College of Arts and Sciences. Her fortnightly column And That’s the Skoop explores student, academic and social culture, as well as national issues, at Cornell. She can be reached at skoh@cornellsun.com.

The Cornell Daily Sun is interested in publishing a broad and diverse set of content from the Cornell and greater Ithaca community. We want to hear what you have to say about this topic or any of our pieces. Here are some guidelines on how to submit. And here’s our email: associate-editor@cornellsun.com.