President Martha Pollack and the University announced official support for the American Dream and Promise Act of 2019 on Monday, according to a University press release.

The bill, introduced as H.R. 6 in the House of Representatives by three Democrats — Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA), Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) and Yvette Clarke (D-NY) — would provide “conditional permanent resident status and a roadmap to lawful permanent resident status and, eventually, U.S. citizenship for” millions of undocumented individuals brought to the country as children, according to the National Immigration Law Center.

A bipartisan Senate version of the bill was introduced in late March of this year by Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Dick Durbin (D-IL).

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program — commonly called “DACA” — was established in 2012 by President Obama via executive order after the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors — or the “DREAM” Act — was proposed several times in Congress but failed to pass.

H.R. 6 represents the newest version of the proposed plan and would expand access to in-state tuition and federal student financial aid for undocumented students, protect against the deportation of high school and college students and extend conditional permanent residence status from eight to ten years to give youths more time to fulfill the conditions of residence.

Pollack wrote to the New York congressional delegation in support of the bill, encouraging each member to vote for the bill when it will likely reach the House floor in early May.

“[Dreamers and TPS students] have already shown that they have the grit and tenacity to overcome challenges and succeed despite long odds. These young men and women deserve to continue their studies, start their careers, and live their lives without the constant fear of disruption or deportation brought on by sudden policy changes,” Pollack wrote in a press release.

Both Pollack and Dean of Students Vijay Pendakur emphasized that undocumented students are “an integral part of the Cornell University Community.”

Rep. Tom Reed (R-NY), Tompkins County’s Congressional representative, however, has expressed strong reservations over similar legislation. In February, Reed pilloried a New York State version of the DREAM Act, calling the now-enacted bill “flat wrong.”

“I am getting sick and tired of hearing from our state capital and political leaders, especially on the left, that say the way to solve the college cost crisis is just more and more taxpayer dollars into these colleges and universities, so we can give the illusion [we’re offering] free college tuition,” Reed said in a conference call with reporters, according to the Finger Lake Times.

According to the Cornell Chronicle, these actions by university officials are part of a national “education advocacy week” that began on April 29 and were organized by the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration — a coalition of U.S. college and university leaders dedicated to raising public awareness for how students and campuses are impacted by immigration policy.

While Cornell students largely approved of the University’s increasingly public posture on the contentious issue, some expressed reservations that Pollack’s calls would actually move the needle.

Tyler Rodriguez ’21, for instance, expressed support for the administration’s stance, but questioned the “amount of institutional support” that the university’s official support for the bill would actually provide to DACA students and Dreamers.

In May 2017, false rumors circulated around Cornell’s campus that Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents were on campus, causing widespread alarm. The rumors were eventually addressed by the administration, but only after hours of university officials declining to comment publicly.

Pollack’s stance on the act, however, fits into a previous pattern of support for undocumented immigrants.

For instance, in August of 2017, when President Donald Trump announced he was considering an end to DACA, Pollack wrote a letter to him, “strongly” urging him to “preserve and defend the DACA program.”

“Cornell University was founded in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War as an institution ‘where any person can find instruction in any study,’ with a commitment to diversity and inclusion from the start,” she wrote.

Trump ultimately rescinded the order almost two years ago, but several court decisions since have kept the endangered program afloat. In August of 2018 a Texas federal judge called the executive order “likely unconstitutional,” but still declined to issue an injunction halting its enforcement, according to National Public Radio.

On September 5, 2017, when the Trump Administration officially announced that it was ending the DACA program, Pollack released a statement on the same day enumerating a list of eight commitments to DACA students, including affirming their eligibility for financial aid, providing on-campus housing options for students concerned about traveling abroad during breaks, and reconvening the Cornell Committee to Support Undocumented Students.

“To each of our students who must now fear for their future, please know that Cornell stands with you,” she wrote.

In January 2018, the university also announced it would provide financial assistance for students applying for renewal of their legal status. The assistance came from the DACA Renewal Fee Emergency Fund, which provided grants of up to $495 to “cover the cost of the renewal application for DACA status, employment authorization and biometric services,” reported the Cornell Chronicle. Around the same time, Cornell Law School also provided free legal assistance to DACA and undocumented students regarding their immigration status.

Even so, some parts of the student body believe Pollack and the university could be doing more. Ailen Salazar ’21, a Cornell DREAM Team member, pointed out that while Harvard University, a peer institution, has “protested and sent emails to prevent the deportation or release of a student,” Cornell has no such protocol in place “aside from contacting CUPD and the Crisis Manager.”

She added that “when talking to the Crisis Manager, their answer is ‘We can’t do anything.’”

“What will the university do if a student is detained and is going to be deported?” Salazar wondered.

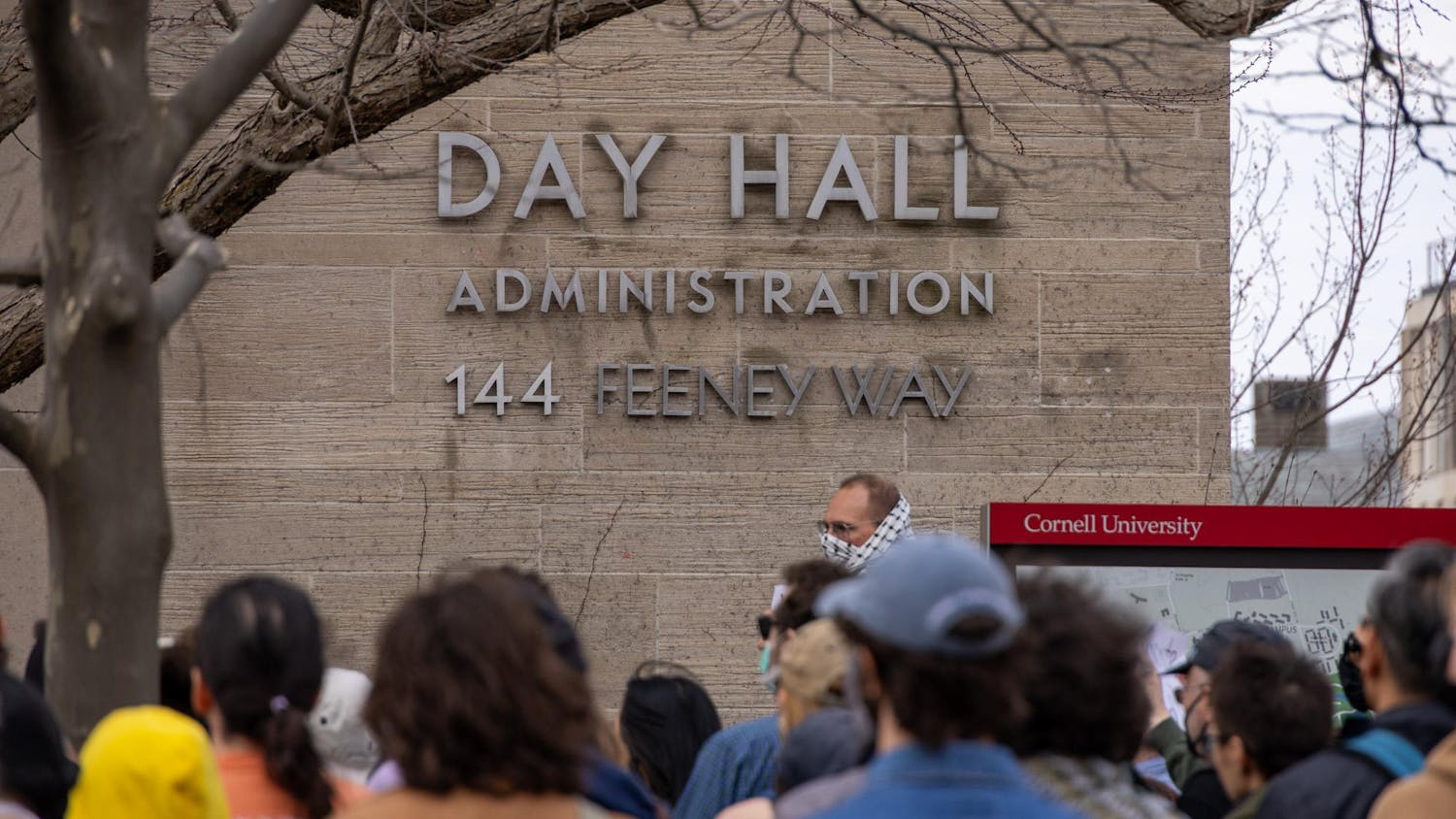

Martha Pollack, University Stands in Support of DREAM Act

Reading time: about 6 minutes

Read More