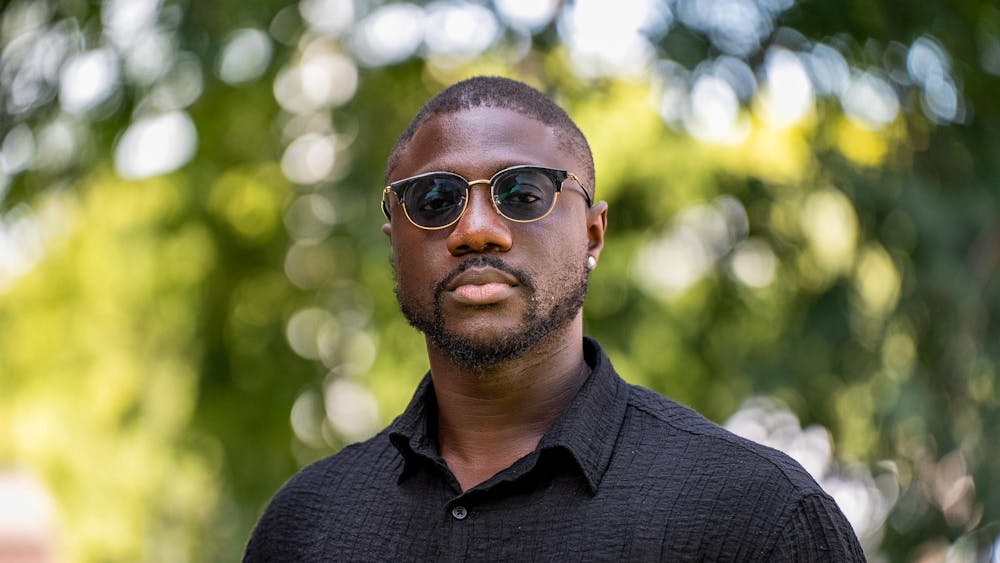

The National Institutes of Health recently awarded Dr. Robert Peck, associate professor of medicine in pediatrics at Weill Cornell, a grant to conduct the first longitudinal study on the relationship between sleep, cardiovascular disease and HIV in Tanzania.

He hopes to gain a better understanding of who gets cardiovascular disease and the outcomes of this diagnosis. Along the way, he also hopes to better understand how to adapt the local, underresourced health systems to fit their communities.

Currently based in Tanzania, Peck serves as a coordinator for the collaboration between Weill Cornell Medicine and Weill Bugando School of Medicine in Mwanza, Tanzania. His efforts in preventative medicine in Africa have landed him this grant to study whether cardiovascular disease is a risk factor for HIV by measuring blood pressure during sleep.

After finishing his pediatrics residency in Boston in 2007, Peck traveled to Tanzania to help establish a new medical school. When he arrived, he noticed there were just as many non-communicable diseases that cannot be transmitted from one person to another, such as kidney disease and stroke, as there were infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and HIV.

“As I walked around the wards, one bed would be a person with HIV. The next bed would be a young person with kidney disease,” Peck said. “The next bed would be one with tuberculosis. The next bed would be someone with a stroke.”

Peck hypothesized that hypertension was the underlying factor for non-transmissible diseases that were being reported in the local Tanzanian hospital since he first came. Witnessing people up to two decades younger (late 30s and 40s) than expected reporting cases of high blood pressure prompted him to dig deeper into his studies of hypertension, prevention and management to shed more light on risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Prof. Justin Kingery, medicine, a co-investigator in the study, got involved in this research this year for similar reasons.

“There are disparities involved in [cardiovascular disease and hypertension] both in and outside of the U.S.” Kingery said. “I also think there are very vulnerable populations like those living with HIV and other diseases, as well, that have an even higher risk than the general population.”

Peck said that because blood pressure varies greatly throughout the day and night, ambulatory blood pressure cuffs — which can measure blood pressure as one moves around in their daily life — would be more useful compared to measuring blood pressure in a single sitting.

Peck added that nighttime blood pressure is a more stable representation of one’s cardiovascular system compared to daytime blood pressure, allowing physicians to gain a more accurate read of the stiffness of a person’s arteries and the efficiency of heart pumping, which both can be key indicators in cardiovascular disease.

According to Peck, this study design will help researchers understand some key cardiovascular abnormalities that can only be seen through 24-hour blood pressure monitoring, such as elevated blood pressure only at night, or masked hypertension — when normal blood pressure is reported in the clinic but blood pressure increases outside of this setting.

This monitoring can also detect nondipping, in which blood pressure does not lower at night as it should, which increases the load on the heart and stress on the brain, Peck explained.

“Those are the patterns we know from high-income populations, but we understand very little of these things in the African context,” Peck said.

Peck’s commitment to reducing the health disparities between lower and higher income countries is one of the reasons that drew Kingery to his work.

As a researcher working alongside Peck for more than six years, Kingery also praised Peck’s community-driven efforts to study this three-way relationship between sleep, cardiovascular disease and HIV to better support Tanzanian and East African communities, which are underrepresented in such scientific studies.

“I think it’s rare to see someone who truly cares about the science, about the humanity, about the clinical care, and all these things ruled into one at the level he does,” Kingery said.

Peck and his co-investigators hope to turn these findings into preventative practices among Tanzanians by working with policy makers at the country’s Ministry of Health. This ongoing process, as he states, reinforces their standard that “prevention is better than treatment.”